In the 1960s, the Royal Botanic Gardens started purchasing lands at a previous sand-mining site in Cranbourne to set up a satellite garden for promoting the cultivation of Australian plants. The Royal Botanic Gardens Cranbourne was hence established in 1970 and now covers 363 hectares of heathlands, wetlands and woodlands.

Its centrepiece attraction is the 15-hectare, $49.5 million Australian Garden which was created to showcase Australian flora, landscapes, art and architecture. More specifically, the Australian Garden is intended to be a place where visitors can:

- appreciate the beauty and diversity of Australian plants.

- explore the evolving connections between people, plants and landscapes.

- discover inspiration and information about how to use Australian plants in their home gardens.

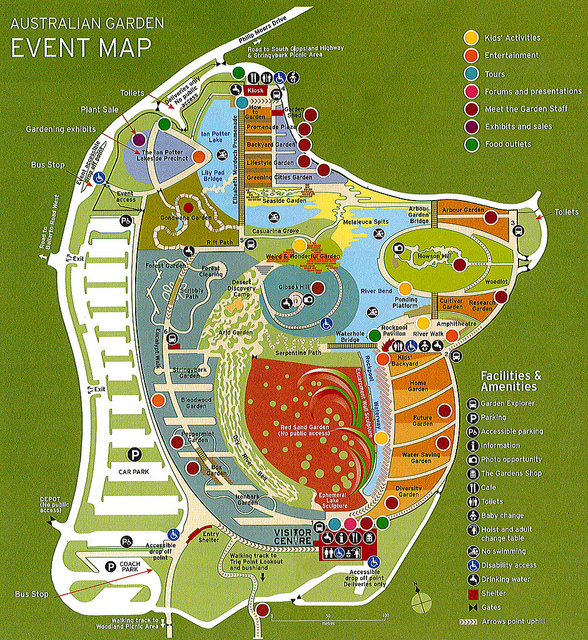

The 9-hectare Stage 1, which concentrated on arid environments and the journey of water, opened on 28 May 2006. The 6-hectare Stage 2, which depicts river systems, coastal and urban environments and forests, officially opened on 19 Oct 2012, ending 20 years of planning, construction and planting. This final stage added 11 new precincts, 170,000 plants from more than 850 plant varieties and new facilities including a visitor kiosk at the northern end of the Garden, boardwalks and viewing platforms on Howson and Gibson Hills, and an amphitheatre for education programs and performances.

Download map here

Garden Design

The Australian Garden was designed by Taylor Cullity Lethlean Landscape Architects and plant designer Paul Thompson. It is a highly-stylized intervention, based on contemporary interpretations and heavy landscaping, in which the designers make no pretence of giving visitors the naturalistic or the wild.

A central theme of the Australian Garden is the story of water and its passage through (and sometimes absence from) the Australian landscape. In the first stage of the Australian Garden, the journey of water begins in the red desert heart of Australia – the Red Sand Garden. The Dry River Bed and the Ephemeral Lake Sculpture highlight the transient nature of water leaving the desert in drought, arriving with unpredictable floods until it arrives in the Rockpool Waterway. In the second half of the Australian Garden (the northern half), the Rockpool Waterway becomes a River Bend at the River Walk.

Red Sand Garden and Ephemeral Lake

The Red Sand Garden is an awe-inspiring interpretation of the desert landscape. It features a vast expanse of vibrant red sand (sourced locally from an old quarry) with circles of saltbush and crescent-shaped mounds designed to echo the shapes and colours found in Central Australia. The red sand contrasts dramatically with the grey foliage of the plantings. On the northern hill, mass plantings of Acacia binervia and the Spinifex sericeus are used to stabilize the sandhills. The lower slopes are covered by a carpet of muntries (Kunzea pomifera), the fruit used for food by the Aborigines. The garden is designed to show seasonal flushes of wildflowers, as seen in the deserts of Central Australia.

The Ephemeral Lake sculpture, shown by the yellowish stripes in the above photo, is created by Mark Stoner and Edwina Kearney, using low relief, liquid-shaped ceramic plates.

The Rockpool Waterway and Escarpment Wall

Designed by Greg Clark, the over 100 metres long Escarpment Wall is inspired by the red sandstone escarpments found in places like Uluru and King’s Canyon. It forms the bank on one side of the Rockpool Waterway, which is a shallow canal dotted with square stepping stones at different heights. The waterway has subtle, angled terraces, so as the water flows, it tumbles over the little shelves from one side to another, like a curtain being drawn or a fringe falling over a face.

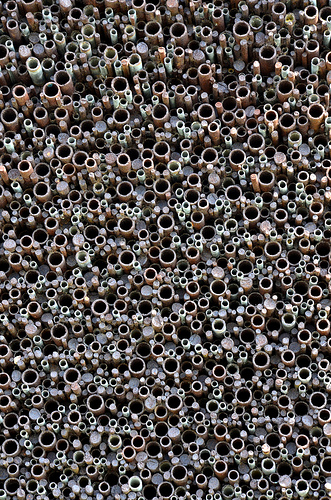

The water descends over a small waterfall into a waterhole where a bridge crosses over to join the Serpentine Path. Past the bridge is a looming sculpture made from oxidized iron.

|

|

Gibson Hill

Another prominent landscape feature, Gibson Hill, is an ideal place to rest with panoramic views to the entire Australian Garden. It will be cloaked with blue-foliaged saltbush and acacias to provide a backdrop to the Red Sand Garden. A winding Serpentine Path provides all-abilities access to the top of the Hill.

View of the Gibson Hill from the Serpentine Path

Weird and Wonderful Garden

Located in the heart of the Australian Garden, this mysterious garden focuses on some of the stranger forms of Australian flora including dramatic plants such as Doryanthes, cycads, Xanthorrhoea, Brachychiton, Flindersia and Livistona. These plants are juxtaposed with massive vaults of Castlemaine stone and water features to create a fantastic and surreal landscape.

I do not think that I had covered this garden entirely during my visit for I did not see the huge Castlemaine vaulted stones and plants such as the cycads and the Queensland Bottle Tree (Brachychiton rupestris). But I did manage to see the very unusual Grass Tree, more popularly known as Blackboy. The following photo shows the Xanthorrhoea johnsonii or Johnsons Grass Tree, which is found in eastern Australia and can grow to 5 metres tall. What makes this tree so visually striking is its very long flower spikes. Flowers are borne on a long spike above a bare section called a scape and the total length can be up to 4 metres long. Flowering occurs in a distinct flowering period, which varies for each species and can be stimulated by bushfire.

Johnsons Grass Trees with their spectacular flower spikes

Melaleuca Spits

The Melaleuca Spits sculpturally and horticulturally represent Australia’s rich and distinctive estuarine coastal topography. Layers of aquatic reeds, sand spits, and bands of Melaleucas provide striking vistas from many other locations within the Garden.

Arbour Garden

An arbour is a framework that supports climbing plants. This garden is so named as it contains a long line-up of wire-grid frames where vertical spaces are used innovatively for supporting native climbers such as gum vines and kennedias, in place of traditional plants such as roses and wisteria. The idea is to create a series of green walls with a verdant tunnel for a pathway, through which children can play hide-and-seek or which brides can pose for spectacular portraits. But right now with the kennedias just establishing, there are more grids than greens to be seen.

Flowering Kennedia macrophylla (also known as Augusta Kennedia)

River Walk

The River Walk is a broad promenade with views across a meandering “river bend” of water. This area, comprising a large, curving, treed walkway of granitic gravel and a waterside section of timber decking, connects the Rockpool Waterway with the vibrant Display Gardens and Howson Hill. A timber-clad amphitheatre with seating for over 150 students provides an outdoor gathering space fringed by Australian plants and shade-providing trees.

Exhibition Gardens

These 5 exhibition gardens demonstrate ways that Australian native plants can be used in the home garden.

- Diversity Garden – illustrates a variety of native plants from various climatic zones in Australia. Water Saving Garden – shows how to group plants with similar water needs and choose plants which require minimum watering in a garden.

- Future Garden – features various alternate ways of gardening, such as special plant choices and novel mulches.

- Home Garden – shows a number of gardens featuring native plants for some common types of homes found in Australia.

- Kid’s Backyard – uses natural plant materials recycled into a children’s play area rather than the common plastic and metal constructions commonly found in Australian backyards.

The Eucalypt Walk

Eucalypts are an omnipresent feature of the Australian landscape, with around 700 species found in virtually all habitats. The Eucalypt Walk features 5 gardens (Ironbark, Box, Peppermint, Bloodwood, Stringybark) displaying some well known eucalypt species.

Little Drumsticks (Isopogon anemonifolius)

After-Visit Thoughts

Having read about the praises that the media heaped on the Garden and learnt of the large number of awards (18) that it had won, I visited the Garden armed with great expectations. However, I left the Garden with more questions than I started with.

Red Spider Flower (Grevillea speciosa)

Firstly, one would expect that a garden that takes a generation (20 years) to develop would be pretty matured. Hence, I was very surprised by the nascent state of the garden. This leads me to think it may take another generation before the trees can be large enough to provide ample shade, by which time only my children and their children can get to enjoy. I do not know why it takes such a long time to develop the Australian Garden. The 101-hectare, S$1 billion Gardens by the Bay in Singapore (Ref 1), which I believe is a much more technically difficult project to achieve, took 5 years to complete and is still expanding. I have not been to this Garden before but photos of the Flower Dome, Cloud Forest and Supertree Grove look very impressive, out-of-the-world and something like from the Avatar movie. Below is a YouTube video of this garden:

Of course, the motivations, objectives and directions of the two gardens are very different. The Australian garden focuses on native plants, which are already best suited to growing conditions in Australia. In contrast, Gardens by the Bay transplant exotic plants from distant parts of the world to Singapore, necessitating the creation of artificial environments such as temperature and humidity controlled facilities and special soil conditions. Gardens by the Bay have proven to be successful as a strong pull for not only local residents but also international tourists. It has become an iconic landmark of Singapore, enhancing its image and is a source of pride for its citizens.

In terms of sustainability, environment-friendliness and running costs, the Australian garden is clearly the more superior. However, in terms of innovation, technology, visual appeal, economic benefits and usage, Gardens by the Bay wins hands-down.

Grass triggerplant (Stylidium graminifolium)

Secondly, I am confused on how the Australian Garden positions itself. Is this meant to be a primarily botanical garden or a landscaped theme park? Most areas of the garden are covered by either sand, concrete or man-made structures. If you divide the total surface area of the garden by the area occupied by plants, I believe the plant cover will be pretty low. I feel that a botanical garden should stick to its conventional emphasis on plants. Any landscaping should function to enhance and complement the showcasing of the plants, not to overshadow them. These artificial elements should always stay in the background, rather than becoming the “main actors“. If a visitor brings away more impressions of the sculptures and features rather than those of the plants, then there is probably a wrong prioritization of the design focus. I have no concerns if this is marketed as a recreational park rather than a botanical garden, which in my opinion, carries educational and conservational responsibilities.

The third concern is the accessibility to plants. The Red Sand Garden occupies a big chunk of the Australian Garden and yet it is off-limit to visitors. You can only view it from afar. It is like watching a picture frame or perhaps better than that, a mammoth garden behind a protected fence. According to the RBG’s website, this garden contains a rich variety of plants which include the Albany Daisy, Kangaroo-paw, Pincushions, Pineapple Bush, Rope-rush, Popflower, Snakebush, Mat-rush, Grass tree and other rockery plants. But from my vantage point, I can only make up patches of greys and greens from among the red sands. Unless with the help of a binocular, I cannot see the individual plants nor learn about their features, although I am very curious what plant forms grow in a desert. The only reason I could think of why this Garden is not made accessible is for the protection of the Red Sand Sculpture. If the Australian Garden’s objective is solely for visitors to admire this award-winning sculpture, then I can understand this arrangement. Otherwise, the garden’s management should think of some ways of allowing access to the Red Sand Garden while not damaging it so that visitors are able to have closer views of the desert plants.

In fact, I enjoyed walking through the Eucalypt Walk as the various gardens there allow me to come into close contact with many plants and flowers (some very exotic looking ones such as the Little Drumsticks and Red Spider Flowers) that I have not seen before.

What strikes me about this botanical garden is the lack of shades. I made my visit on the Open House Day which was in the middle of Spring when the maximum temperature was supposed to be 20 degrees Celsius. However, I was soon sweating and parching under the direct sunlight. You may argue that one must be patient and allow enough time for the trees to grow. But I think the design does not place an emphasis on the provision of ample shady trees. Most open spaces, including those around the water, are either concreted or covered in sand. The tree saplings being planted are too sparse and scattered to provide substantial cover. I would not be excited in visiting the Australian Garden during summer and on hot days. I believe one of the criticisms of the Birrarung Marr Park is that it is often a sun-baked area and hence, not inviting. I would like the Australian Garden to be less harsh and more generous with foliage.

Dr Philip Moors, director and chief executive of the Royal Botanic Gardens, describes the Australian Garden as a garden for the community and a means of inspiring visitors to develop their own spaces. I will like the Australian Garden to be a social space – a place people will not find intimidating, that will tempt them to spend time relaxing there. You would see that spaces popular with people such as the city’s botanical garden and Flagstaff gardens usually have extensive lawn areas accompanied by a fair amount of tree shades. I do not know why the Australian Garden hardly has any lawn areas. Perhaps the designers think that lawns should only have their places in a European-style garden and will thus be awkward in a garden with an indigenous theme. But I think all people love well-manicured lawns. These include Asians in which lawns are not part of their traditional gardens. Lawns are pleasant to look at, lie down and would confer a soft edge to the domineering hard architectural elements in the Australian Garden.

The architectural design can evoke different feelings in different people. To the architecturally-illiterate, the landscaping and sculptures may not mean much. For example, the Rockpool Waterway and the various man-made lakes are too artificial for me. They remind me of the opulent water features in mega shopping malls or in “Las Vegas” style of palatial casinos. I do not think the much-photographed Shelter in the Lifestyle Garden (see above) serves any practical function for it will not protect you from the sun or rains. Appearance-wise, it looks like a “flexible” version of a brown timber cabinet door with vents.

The name of the Garden itself can stimulate much ponderings. Exactly what is meant by “Australian” – what do people identify as a nation? The creators of this Garden have associated the “Australian” theme with native plants and Aboriginal art forms. To some, “Australian” may mean multiculturalism and diversity. Yet others may interpret this to be things that they are familiar with and can relate to in everyday lives. Hence, the Australian Garden which includes stuff such as the Gondwana Garden (during the Triassic Era) and the Red Sand Garden would probably be exotic and remote from most people’s typical experiences. Thus, it will be a challenge if the Australian Garden is aiming to make a real-life connection with the visitors.

Thanks for this blog!!

your blog is very informative.

Turf Sydney